SWIM: The scalable membership protocol

In a distributed system we have a group of nodes that need to collaborate and

send messages to each other. To achieve that they need to first answer a simple

question: Who are my peers?

That’s what membership protocols do. They help each node in this system to

maintain a list of nodes that are alive, notifying them when a new node joins

the group, when someone intentionally leaves and when a node dies (or at least

appears to be dead). SWIM, or Scalable Weakly-consistent

Infection-style Process Group Membership Protocol, is one of these

protocols.

Understanding the name

Scalable Weakly-consistent Infection-style Process Group Membership Protocol is quite a long name for a protocol that seems to do such a simple thing, so let’s break down the name and understand what each piece means. This will also help us understand why this protocol was created in the first place.

Scalable: Prior to SWIM most membership protocols used a heart-beating

approach, that is, each node would send a heartbeat (i.e. an empty message that

just means “I’m alive!”) to every other node in the cluster, every interval T.

If a node N1 doesn’t receive a heartbeat from node N2 after a certain

period, it declares this node dead. This works fine for a small cluster, but as

the number of nodes in this cluster increases, the number of messages that need

to be sent increases quadratically. If you have 10 nodes, it may be fine to send

100 messages every second, but with 1,000 nodes you would need to send

1,000,000 messages, and that would not scale very well.

Weakly-consistent: That means that at a given point in time different nodes can have a different view of the world. They will eventually converge to the same state but we cannot expect strong consistency.

Infection-style: That’s what is also commonly known as a gossip or epidemic protocol. It means that a node shares some information with a subset of its peers, that then share this information with a subset of its own peers, until the entire cluster receives that information. That means a node doesn’t need to send a message to all of its peers, it just tells that to a few nodes that will gossip about it.

Membership: Well, that basically means we will ultimately answer the question “Who are my peers?”

SWIM Components

Heart-beating protocols usually solve 2 different problems with the heartbeat

messages: They detect when a node fails (because it stops sending the

heartbeat), and they keep the list of the peers in the cluster (that is, every

node that is sending a heartbeat).

SWIM decided to take the novel approach of dividing these 2 problems in

different components, so it has a failure detection and a dissemination module.

Failure Detection

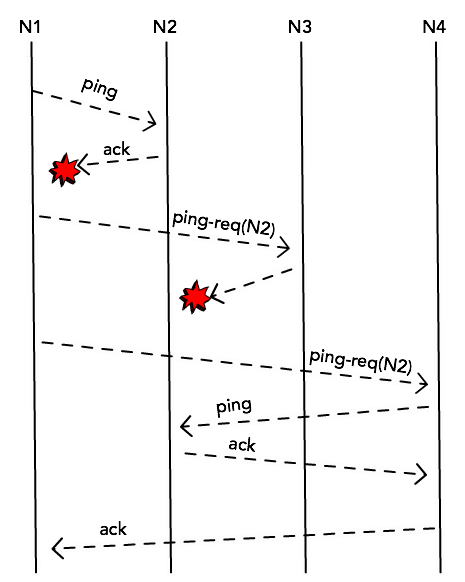

Each node in the cluster will choose a node at random (say, N2) and will send

a ping message, expecting to receive an ack back. This is simply a probe

message and in normal circumstances it would receive this ack message and

confirm that N2 is still alive.

When that doesn’t happen, though, instead of immediately marking this node as

dead, it will try to probe it through other nodes. It will randomly select k

other nodes from its membership list and send a ping-req(N2) message.

This helps to prevent false-positives when for some reason N1 cannot get a

response directly from N2 (maybe because there’s a network congestion between

the two), but the node is still alive and accessible by N4.

If the node cannot be accessed by any of the k members, though, it’s marked as

dead.

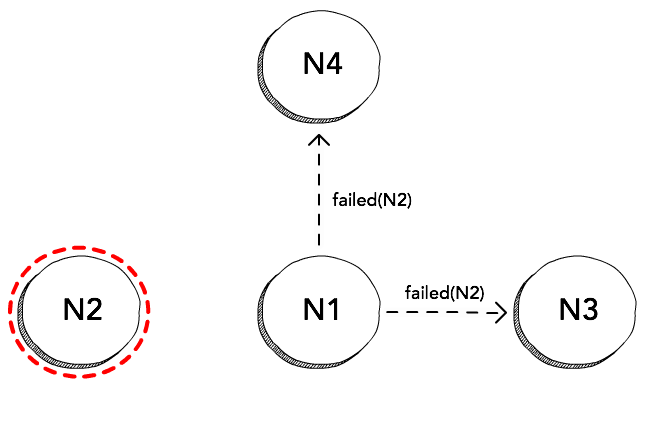

Dissemination

Upon detecting a node as dead, the protocol can then just multicast this

information to all the other nodes in the cluster, and each node would remove

N2 from its local list of peers. Information about nodes that are voluntarily

leaving or joining the cluster can be multicast in a similar way.

Making SWIM more robust

This makes for a quite simple protocol, but there a few modification that the original SWIM paper suggests to make it more robust and efficient, they are:

- Change the dissemination component to use an infection-style approach, instead of multicasting (after all, that’s in the name of the protocol);

- Use a suspicion mechanism for the failure detection to reduce the false positives;

- Use a round-robin probe target selection instead of randomly selecting nodes.

Let’s explore each of these points to understand what they mean and why that would be an improvement over the protocol that we have discussed thus far.

Infection-style dissemination

There are (at least) two issues that we need to be aware of when using this multicast primitive to disseminate information:

- IP multicast, although generally available, is usually not enabled in most environments. For example, if you are running on Amazon VPC, you are out of luck. You would then need to use a pretty inefficient point-to-point solution;

- Even if you can use this type of multicast, it will usually use

UDP, that’s a best-effort protocol, meaning the network can (and probably will) drop packets, making it hard to maintain a reliable membership list.

A better (and, in my opinion, quite elegant) solution suggested in the SWIM

paper is to forget about this multicast idea, and instead use the ping,

ping-req and ack messages that we use for failure detection to piggyback

the information we need to disseminate. We are not adding any new messages, just

leveraging the messages that we already send, and “reusing” them to also

transport some information about membership updates.

Suspicion mechanism for failure detection

Another optimization is to first suspect a node is dead, before declaring it dead. The goal here is to minimize false positives, as it is usually preferable to take longer to detect a failed node than it is to wrongly mark a healthy node as dead. It is a trade-off, though, and depending on the specific case this might not make sense.

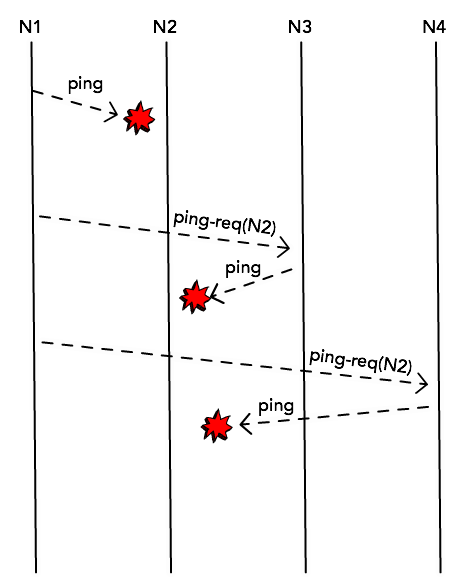

It works like this: When a node N1 cannot receive an ack message from node

N2 (neither directly, through a ping message, nor indirectly, through a

ping-req message), instead of disseminating that N2 is dead and should be

removed from the membership list, it just disseminates that it suspects that

N2 is dead.

This suspected node is treated like a non-faulty node for all effects, and it

keeps receiving ping messages like any other member. If any node can get an

ack from N2, it’s marked again as alive and this information is

disseminated. N2 itself can also receive a message saying it’s suspected to be

dead and tell the group that they are wrong and that it never felt better.

If after a predefined timeout we don’t hear from N2, it’s then confirmed to be

dead and this information is disseminated.

Round-Robin probe target selection

In the original protocol definition the node that is selected to be probed (i.e.

the node we send a ping message, expecting an ack in return) is picked at

random order. Although we can guarantee that eventually a node failure will be

detected by every non-faulty node, this can take a relatively long time if we

are out of luck with our target selection. A way to minimize this problem is to

maintain a list of the members we want to probe, and go through this list in a

round-robin fashion, and new joiners can be added at a random position in this

list.

Using this approach we can have a time-bounded failure detection, where in the

worst case it will take probe interval * number of nodes to select this faulty

node.

Summary

SWIMis a membership protocol that helps us know which nodes are part of a cluster, maintaining an updated list of healthy peers;- It divides the membership problem into 2 components: Failure detection and dissemination;

- The failure detection component works by selecting a random node and sending it a

pingmessage, expecting anackin return; - If it does not receive an

ack, it selectskpeers to probe this node through aping-reqmessage; - An optimization of this failure detection is to first mark a node as “suspected”, and mark it as dead just after a timeout;

- We can disseminate membership information by piggybacking the failure detection messages (

ping,ping-reqandack) instead of using a multicast primitive; - A way to improve the failure-detection time is to select nodes in a round-robin fashion instead of selecting nodes at random.

Other resources

The original

paper

is short and very readable. Serf, a HashiCorp tool, uses SWIM and has a

nice overview in their

documentation. They also talk about some modifications they made to increase

propagation speed and convergence rates, and the code is open source.

Armon Dadgar, one of HashiCorp’s co-founders, also gave a very nice talk

explaining the protocol and these modifications:

Interested in learning Kubernetes?

I just published a new book called Kubernetes in Practice, you can use the discount code blog to get 10% off.