Speaking Rabbit: A look into AMQP's frame structure

RabbitMQ supports several different messaging protocols, but there is no doubt that AMQP (0-9-1) is the one most commonly used (and what RabbitMQ

was originally developed for).

It’s AMQP that defines how exchanges, queues, binding and most of the things that you, as an application developer, usually have to work with.

AMQP is conceptually divided in two layers, the functional and the transport. Here I want to talk about an important part of the transport layer: Framing.

You will not normally need to deal directly with RabbitMQ’s frames, unless you are

building a client library, but that’s the foundation of every kind of communication that happens between your application and the broker, so getting a bit more familiar

with how things work under the hood doesn’t hurt. Also, next time you see an unexpected_frame error in your logs you will have a clue of what is going on.

The anatomy of a frame

A frame is AMQP’s basic unit. They are the chunks of data that are used to send information from RabbitMQ to your application and vice-versa. Let’s first take a look

at what a frame looks like and what are all the different types of frames that can be used.

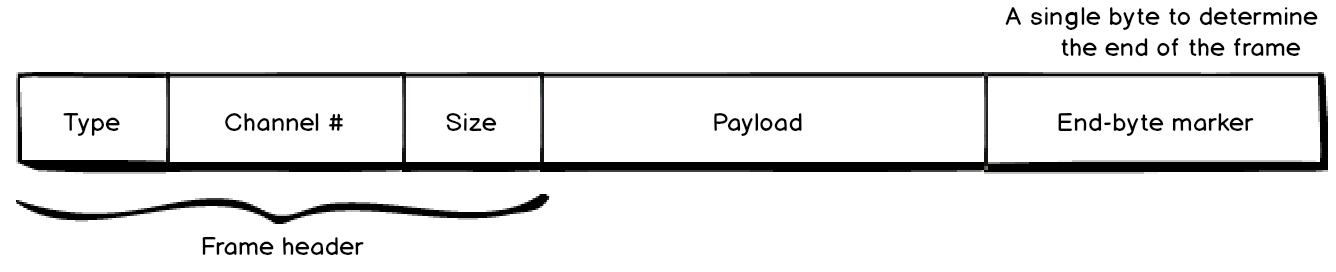

Every frame will have the same basic structure:

These are the five parts of a frame, the first three being its header, followed by a payload and an end-byte marker, to determine the end of the frame.

The header defines the type of frame (one of the 5 listed bellow), the channel this frame belongs to, and its size, in bytes.

The payload varies accordingly with the frame type, so each type of frame will have a different payload format.

The frame types

There are 5 types of frames defined in the AMQP specification, they are:

-

Protocol header: This is the frame sent to establish a new connection between the broker (

RabbitMQ) and a client. It will not be used anymore after the connection. -

Method frame: Carries a RPC request or response.

AMQPuses a remote procedure call (RPC) pattern for nearly all kind of communication between the broker and the client. For example, when we are publishing a message, our application callsBasic.Publish, and this message is carried in a method frame, that will tellRabbitMQthat a client is going to publish a message. -

Content header: Certain specific methods carry a content (like

Basic.Publish, for instance, that carries a message to be published), and the content header frame is used to send the properties of this content. For example, this frame may have the content-type of a message that is going to be published and a timestamp. -

Body: This is the frame with the actual content of your message, and can be split into multiple different frames if the message is too big (131KB is the default frame size limit).

-

Heartbeat: Used to confirm that a given client is still alive. If

RabbitMQsends a heartbeat to a client and it does not respond in timely fashion, the client will be disconnected, as it’s considered dead.

And that’s pretty much everything there’s to know about AMQP’s frames: 5 possible frame types, each frame being divided in 5 parts, that will allow your application and

RabbitMQ to talk about everything they need to know from each other. It’s also interesting to notice that AMQP is a bidirectional protocol, unlike HTTP, meaning both

RabbitMQ and your application can send remote procedure calls.

Now that we now what’s happening behind the curtains of our client libraries, let’s recap what happens when we publish or consume messages.

Publishing and consuming messages

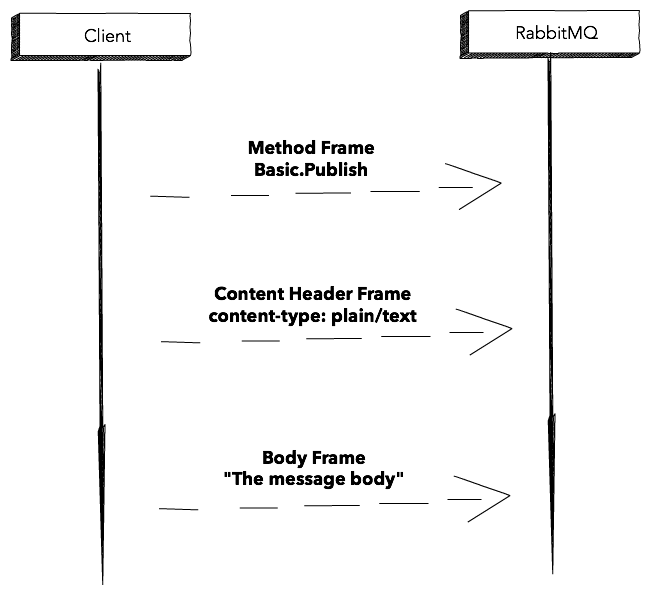

When publishing a message, the client application needs to send at least 3 frames: The method (Basic.Publish), the content header, and one or more body

frames, depending on the size of the message:

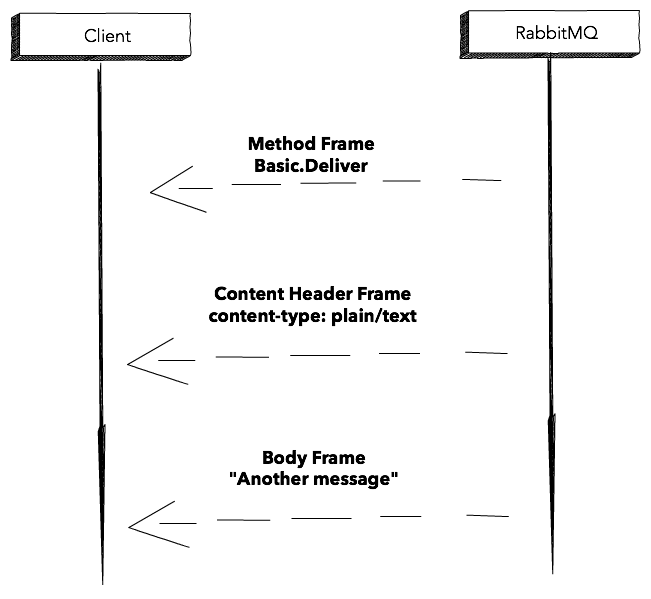

And consuming messages is pretty much the same thing, but it’s the broker, RabbitMQ, that sends the frames to our client application:

Diving deeper

This was a very short overview of the way RabbitMQ sends data over the wire. To get more information about how AMQP works, the

specification is quite readable and not that long. For a more RabbitMQ-specific approach,

RabbitMQ in Depth is also a great resource.

Interested in learning Kubernetes?

I just published a new book called Kubernetes in Practice, you can use the discount code blog to get 10% off.