Exponential Backoff in RabbitMQ

RabbitMQ is a core piece of our event-driven architecture at AlphaSights. It makes our services decoupled from each other and extremely easy for a new application to

start consuming the events it needs.

Sometimes, though, things go wrong and consumers can’t process a message. Usually there are two reasons for that: Either we introduced a bug that is making our worker fail or this worker depends on another service that is not available at the moment.

There are normally three ways to handle failures in RabbitMQ: Discarding the message, requeuing it, or sending it to a dead-letter exchange.

Assuming all the messages we receive are important, we can’t just discard them, so we have two options left.

The problem in requeuing

This was our initial approach, every time a message fails, we just requeue it so we can try to process it again.

Although this can be a valid solution for simple scenarios, in our case it caused more problems than it solved.

In cases where our worker is broken, just trying to process the same message again won’t help, it will just keep failing over and over again

(and creating a lot of noise in your monitoring tools). The worst problem, though, is when we DDoS another service. If this service is not available due to period of

high load, sending it thousands of requests is not a very good idea.

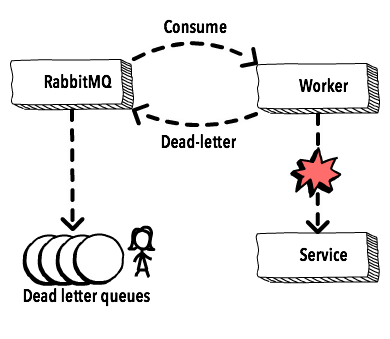

The problem in dead-lettering

The second approach was to just send the failed messages to a dead-letter exchange, that would route it to a resting queue that we need to manually handle. After the problem

is identified, we can shovel the message back to the working queue to be processed, or we can just reject the message if it doesn’t make sense to consume it anymore, that way we never

DDoS other services.

The problem now is that we have a manual step. A lot of times the failure is caused just by an intermittent issue, like a timeout, that would be solved if the message was processed again in a few seconds (or minutes).

Enters the exponential backoff strategy

Given these issues we were facing, having an exponential backoff strategy was the logical solution. We would not DDoS other services, and for intermittent failures, the messages would be automatically retried,

avoiding the need for a manual intervention when this is not necessary. Implementing this strategy, though, was not as straightforward as we thought.

We started by looking at what other people were doing.

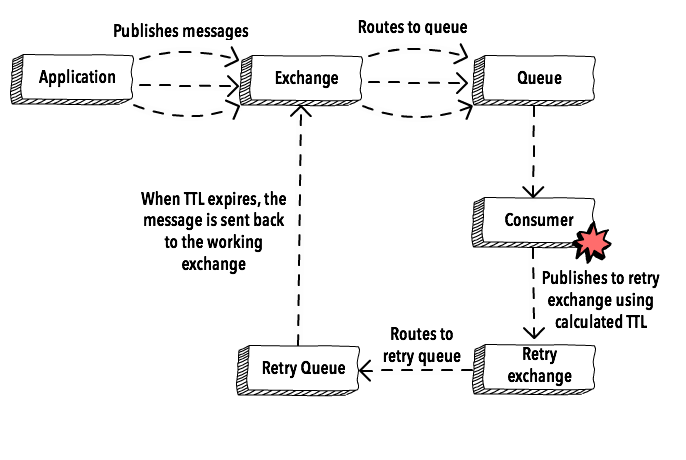

The common approach seems to be to use a retry exchange with a per-message ttl. It works somewhat like this:

Once you understand how RabbitMQ handles time to live (TTL) and dead-letter exchanges, the implementation is straightforward:

-

We have two exchanges: The working and the retry exchange;

-

The working exchange is defined as the dlx for the retry exchange;

-

Based on how many times the message fails, we calculate the

TTLfor this message. For example, the first time the message fails we publish it with aTTLof 1000ms, if it fails again we publish aTTLof 2000ms, and so on; -

Given that the working exchange is the dlx for the retry exchange, when a message reaches its time to live and is automatically rejected, it goes to the working exchange and is consumed again.

The problem

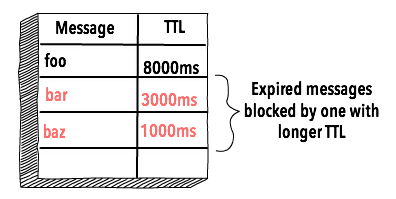

As you probably guessed, there’s also a problem with this common approach, and it has to do with the way RabbitMQ handles expired messages. From the documentation:

While consumers never see expired messages, only when expired messages reach the head of a queue will they actually be discarded (or dead-lettered). When setting a per-queue TTL this is not a problem, since expired messages are always at the head of the queue. When setting per-message TTL however, expired messages can queue up behind non-expired ones until the latter are consumed or expired.

What this means is that a message will only be dead-lettered when it reaches the top of the queue, so if we have one message with a TTL of 5 minutes and another message with a TTL of 1 second, the first

message will block the rest of the queue, and the second message will only be dead-letter (and executed again), after the first message expires.

The reason is that RabbitMQ queues are always “first-in first-out”, so the time to live will just tell RabbitMQ if it should send this message to a consumer or if it can safely reject it. As

the retry queue doesn’t have any consumer, the message just hangs there until it can be safely rejected.

That makes this solution impracticable, as messages with a high TTL would block messages that should be executed again shortly after they failed. So the quest continues.

And, finally, our solution

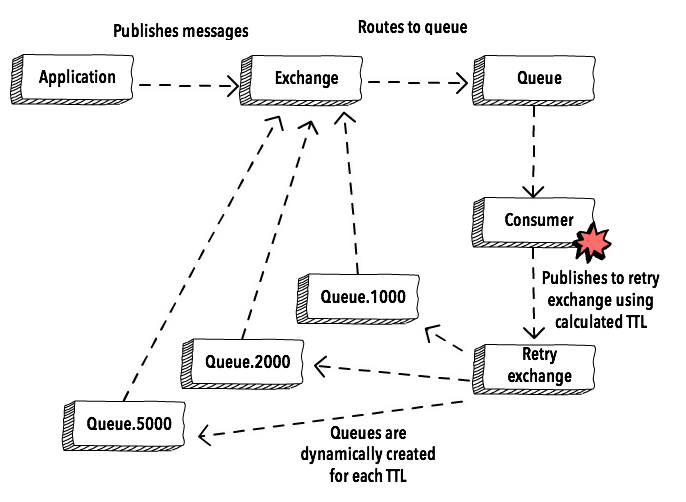

To solve this problem we came up with a solution that is very similar, but tackles this issue by dynamically creating new queues for each TTL value we have.

The main difference here is the creation of new queues for each TTL we have. This solve the problem with blocked messages because now every message that goes to, say, queue.5000, are message with a TTL of

5000ms, so the first message in the queue will always be the next message to expire. The rest all continues the same, when a message in any of these queues expires, it will be dead-lettered and consumed again.

To avoid keeping a bunch of empty queues after all messages are consumed, we also define these dynamically created queues with an x-expires argument, meaning that after the last message is removed from this queue, the queue

itself is also deleted.

Show me the code

If you are disappointed that all you saw until now is a bunch of diagrams, here

is the code we are using. It’s a Sneakers handler that does its magic every time a message fails.

The implementation, though, is just a detail, once you understand the architecture it should be simple to apply this to any other language.

Conclusion

We try to make our pipes as dumb as possible, and at first we had our doubts if this was adding too much complexity. In the end, though, it’s all about finding the right balance. This solution does make the messaging system a little bit less dumb, but just enough to make our systems more reliable (and our lives easier), which is what really matters.

Interested in learning Kubernetes?

I just published a new book called Kubernetes in Practice, you can use the discount code blog to get 10% off.